Monday, January 30, 2017

Sunday, January 29, 2017

Saturday, January 28, 2017

Friday, January 27, 2017

Thursday, January 26, 2017

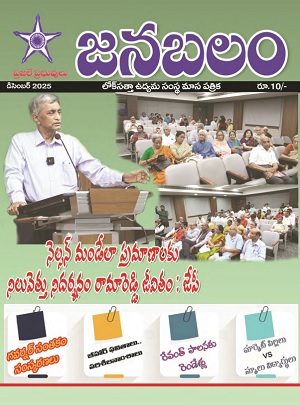

Special status for Andhra, and protest at Vizag beach: Jayaprakash Narayan speaks to TNM

The clamour for special status for Andhra Pradesh is growing on social media, and the people of the state are planning a massive protest in Vishakapatnam on Republic Day, on the lines of the jallikattu protests at Marina beach in Chennai last week.

Lok Satta party founder Jayaprakash Narayan has now joined the voices demanding special status, and in an interview to TNM, the leader says that a political solution is the only way out.

Jayaprakash Narayan is among the many political leaders who are now speaking up on the issue. Joining the hashtag #APDemandsSpecialStatus, he took to Facebook to say that "It is time we stand united and achieve our right."

“The special category status was a solemn promise made by the Prime Minister on the floor on the Parliament. It was not a casual remark,” Jayaprakash told TNM. “The circumstances were also unique. The Parliament bulldozed the state and forcefully divided it,” he said, referring to the bifurcation of the state into Telangana and Andhra.

"Now that bifurcation has happened, in some way or the other, it is necessary to honour that commitment," he added.

Accusing the Centre and the State of not doing enough for Andhra, Jayaprakash said that while mobilising people for a protest will bring visibility to the issue, the only way to resolve the issue was to find a political solution.

“A lot of time has passed after the partition of the state. As time elapses, it becomes more difficult to achieve the special status," he said.

"The real solution would be to sit down with state governments and the Centre and discuss a proposal that would be seen as a zero sum game," he added. "If Andhra gets it, other states will ask for it too."

Following the protest that was organised at Chennai's Marina beach, many Andhra youth want to replicate the silent stand at RK beach. Thousands are expected to gather at the beach on January 26, in support of the cause.

Jayaprakash however says that the protests are unlikely to bring any solution to the issue.

Comparing it to the recent protests in Tamil Nadu, Jayaprakash said, “In the case of Jallikattu, it was a local cultural sentiment. The rest of India had no opposition to the sport in a political sense. Rather, the protestors were animal welfare activists and their kind. However, in this case, there will be political opposition because the concessions and tax exemptions will come at a cost to the other states."

In September last year, massive protests broke out all over Andhra, after Union Finance Minister Arun Jaitley announced a 'special economic package' for Andhra Pradesh, instead of ‘special status’ that the state had demanded.

When asked about the differences between the two, Jayaprakash says, "The special package given to the state does come with benefits. There are benefits in infrastructure, education and healthcare besides a national project status to Polavaram. It is welcome and positive. However, for investment and jobs, we need some kind of tax exemptions, which are provided as part of the special status."

A photo put up by him on Facebook, explains it better.

Alternatively, Jayaprakash also proposes that there could be special financial aid and industrial tax incentives for backward districts in Andhra, and other states, thereby keeping all the stakeholders happy.

Courtesy: The News Minute

Lok Satta party founder Jayaprakash Narayan has now joined the voices demanding special status, and in an interview to TNM, the leader says that a political solution is the only way out.

Jayaprakash Narayan is among the many political leaders who are now speaking up on the issue. Joining the hashtag #APDemandsSpecialStatus, he took to Facebook to say that "It is time we stand united and achieve our right."

“The special category status was a solemn promise made by the Prime Minister on the floor on the Parliament. It was not a casual remark,” Jayaprakash told TNM. “The circumstances were also unique. The Parliament bulldozed the state and forcefully divided it,” he said, referring to the bifurcation of the state into Telangana and Andhra.

"Now that bifurcation has happened, in some way or the other, it is necessary to honour that commitment," he added.

Accusing the Centre and the State of not doing enough for Andhra, Jayaprakash said that while mobilising people for a protest will bring visibility to the issue, the only way to resolve the issue was to find a political solution.

“A lot of time has passed after the partition of the state. As time elapses, it becomes more difficult to achieve the special status," he said.

"The real solution would be to sit down with state governments and the Centre and discuss a proposal that would be seen as a zero sum game," he added. "If Andhra gets it, other states will ask for it too."

Following the protest that was organised at Chennai's Marina beach, many Andhra youth want to replicate the silent stand at RK beach. Thousands are expected to gather at the beach on January 26, in support of the cause.

Jayaprakash however says that the protests are unlikely to bring any solution to the issue.

Comparing it to the recent protests in Tamil Nadu, Jayaprakash said, “In the case of Jallikattu, it was a local cultural sentiment. The rest of India had no opposition to the sport in a political sense. Rather, the protestors were animal welfare activists and their kind. However, in this case, there will be political opposition because the concessions and tax exemptions will come at a cost to the other states."

In September last year, massive protests broke out all over Andhra, after Union Finance Minister Arun Jaitley announced a 'special economic package' for Andhra Pradesh, instead of ‘special status’ that the state had demanded.

When asked about the differences between the two, Jayaprakash says, "The special package given to the state does come with benefits. There are benefits in infrastructure, education and healthcare besides a national project status to Polavaram. It is welcome and positive. However, for investment and jobs, we need some kind of tax exemptions, which are provided as part of the special status."

A photo put up by him on Facebook, explains it better.

Alternatively, Jayaprakash also proposes that there could be special financial aid and industrial tax incentives for backward districts in Andhra, and other states, thereby keeping all the stakeholders happy.

Courtesy: The News Minute

Labels:

english

Tuesday, January 24, 2017

క్షతగాత్రులకు నష్ట పరిహారం పెంచాలి

Labels:

AndhraJyothy,

telugu

Monday, January 23, 2017

Sunday, January 22, 2017

Monday, January 16, 2017

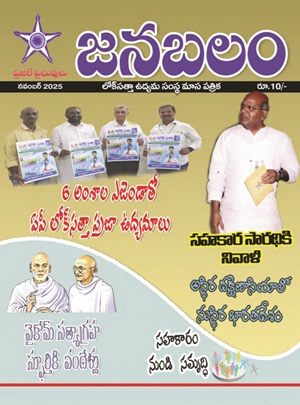

Lok Satta Times Jan 16th-31st, 2017

Lok Satta Times Jan 16th-31st, 2017 can be downloaded from the following link.

http://ap.loksatta.org/documents/lstimes/lstimes-2017-01-16-31.pdf

http://ap.loksatta.org/documents/lstimes/lstimes-2017-01-16-31.pdf

Monday, January 9, 2017

Sunday, January 8, 2017

2017 Wishlist: How We Can Transform India With These 5 Big Doable Tasks That Cost Only 1% Of GDP

The demonetisation drive launched by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and the developments witnessed since 8 November, 2016 are very instructive to every citizen ardently wishing for a better India. Demonetisation is a well-intended bold move touching practically every citizen and aimed at rooting out black money and curbing corruption. It is too early to make informed judgments about the eventual outcomes. But there are already certain early signs: about 90 per cent of the high-value old currency has been deposited in banks; most ordinary citizens have had to endure hardship on account of the failure to make available new currency in exchange for the old; arbitrary, ad hoc decisions on a daily basis have induced fear, uncertainty, mistrust and even ridicule; ubiquitous corruption and a vast, efficient network of parallel economy can be seen or inferred; and trust between the citizen and banking system has been eroded.

We may dismiss them as unintended consequences of a momentous decision touching all people in a vast and diverse nation. But all these travails also expose the capacity deficit of the Indian State, lack of accountability, cavalier and contemptuous treatment of ordinary citizens in daily life, and the general failure of governance as perceived by the citizens. Clearly, the governance crisis cannot be effectively addressed by one person at the helm; it encompasses all branches and tiers of governance.

Those of us who are fortunate by circumstances and are insulated from the vagaries of our day-to-day governance view everything through a party-political prism. But ordinary citizens approach government offices on a daily basis for myriad services - ration card, birth certificate, record of land rights, registration of sale of a property, water or power connection, building permission, assessment of property tax, filing a first information report in a police station or going to the court in a civil dispute. In each of these instances we witness delay, harassment, humiliation, corruption, sheer incompetence and contempt for the citizen.

Almost all key services we expect the government to deliver in return for the taxes we pay - basic housekeeping, land administration, water, stormwater drainage, sewerage, electricity, traffic management, police, courts, education, healthcare - are in shambles relative to any other major economy in the world and, more important, relative to our potential and ambition as a nation. It is no wonder that almost uniquely among all major economies, Indian elites do not depend on the government for almost any service - water, power, transport, security, education, healthcare - and have gone to extraordinary lengths to insulate themselves from all-round governance failure.

This brings us to two important but related questions: Are we a singularly ungovernable people needing authoritarian political systems to control us? Is there a precipitous decline in values after Independence that brings the worst out of us and makes anarchy and corruption endemic to our society?

I argued in a 2005 paper, "Good Governance in the 21st century", that values such as honesty, trust, sacrifice, cooperation and reciprocity are very strong within a family, caste or other close-knit social groups in India, and it is not their absence that is bedeviling us. It is the incapacity to transfer these values beyond traditional groups to the larger Indian society that manifests in nepotism, corruption, criminalisation of politics and mis-governance. It is the function of the governance system to reward and encourage socially productive, desirable behaviour, and discourage deviant behaviour. As William Gladstone, the 19th century British statesman, aptly said, "the purpose of a government is to make it easy for people to do good, and difficult to do evil." It is our failure to design institutions to serve this purpose and to hold our state functionaries - politicians, bureaucrats or judges - to account that is at the heart of our crisis, not the follies of our people.

Our freedom fighters and nation builders did a remarkable job in successfully welding the world’s most diverse peoples into one nation, and building functioning democratic institutions. The results, in many ways, are astounding. Despite seemingly insurmountable obstacles, and despite being the first nation to embrace universal franchise with abject poverty and vast illiteracy, freedom has been preserved, peaceful transfer of power through the ballot has been institutionalised, a very successful and mature federalism has evolved, unity has been strengthened in a complex, unimaginably diverse, multi-ethnic, multi-lingual society and moderate economic progress has been witnessed. The way we dealt with linguistic diversity and are able to harmoniously function as one nation with 22 languages is nothing short of a miracle in the modern world, and is a tribute to our people’s common sense, pragmatism and tolerance, and our leaders’ wisdom and foresight.

Clearly, where we had designed systems well and acted with good sense, we succeeded brilliantly. The corollary is, where we designed institutions poorly and created perverse incentives, the system malfunctioned with grievous consequences.

Every society has its strengths and weaknesses. The governance system must build on strengths and correct weaknesses. In our case, certain institutional and cultural flaws that are inimical to democracy have not been adequately corrected during our republican journey, leading to the undermining of the democratic process and serious governance deficit.

We inherited three initial conditions that have not been corrected even today.

The first is asymmetry of power between the citizen and the public servant. Abject poverty, colonial legacy and a mostly agrarian economy meant that even the lowliest government employees are more economically secure, influential and powerful than most citizens. This was compounded by the disastrous license-permit-quota Raj and state control of most economic activity, and made the bureaucrat the master and the citizen the mendicant. As a result, poor delivery of services, harassment, corruption and influence peddling have become integral features of our governance.

The second initial condition is the absence of a notion of citizenship, thanks to centuries of tyranny or colonial rule, relatively sudden transfer of power from the British without real and adequate experience in self-governance, and our cultural propensity to worship hierarchies and power. As a result, elected leaders are seen as "monarchs" who will somehow deliver. Citizens were never enabled to discover the links between taxes and services, and vote and public good. Except that the new "masters" are elected, the people are still "subjects" and those in power are "mai baap".

The third initial condition is a high degree of centralisation with little space for local management of issues and no possibility of correction of distortions, leadership development or experimentation and innovation in a diverse nation.

These initial conditions led to most of our current governance crisis: over-reliance on elected legislators to somehow "deliver" with a vast parallel party machinery; failure to hold the bureaucracy to account locally and consequent poor services; vast cost of maintenance of a parallel machinery and corruption; mounting perpetual voter disaffection; use of money or short-term freebies to entice the angry voter each time; the increasing role of illegitimate money power in elections; de-linking of votes from public good and tangible consequences; manipulation of primordial loyalties and sentiments of caste, region or religion to obtain votes; political recruitment from dynasties and corrupt moneybags to somehow win power. All these are, in many ways, attributable to our failure to address the three initial conditions that are inimical to democratic governance and competent delivery.

Now that Prime Minister Modi has shown that he can break out of traditional moulds, my hope and expectation is that in 2017 and in the years after, thoughtful, systematic, innovative steps will be initiated to end this vicious cycle and generate a virtuous cycle creating the right incentives, promoting trust and citizenship, improving services and enforcing accountability. This is necessarily a slow, complex process in a vast and diverse country with enormous baggage of the past. But the positive outcomes of over two decades of partial economic reform have shown what Indians can achieve. A series of well-designed, interconnected, politically feasible, economically viable, socially acceptable institutional reforms will most certainly accelerate the emergence of this virtuous cycle and transform governance.

This essay assumes that, in the wake of demonetisation, the government will follow up on key issues of reform to end the generation of black money, especially reform in the real estate sector to help citizens come out of cash transactions, address petty corruption as well as grand corruption through a series of well-coordinated steps, and begin the process of building political consensus on creating conditions to make the best electable without vote buying.

Based on that very big assumption, here are the five big changes I would like to see in the near future.

First, improve service delivery and enforce accountability in the bureaucracy. Our service delivery is appalling and corruption is ubiquitous and endemic in almost every interface with bureaucracy. Taxation without services is nothing but legal plunder.

Willing compliance of the vast majority of citizens is the foundation of a modern state; not coercion and letting loose the arbitrary officials on the long-suffering people.

A service guarantee law should be enacted to ensure timelines and compensation for delays to end day-to-day coercive corruption and harassment; the utterly ludicrous proposals to harshly punish small bribe givers who are victims of extortion and provide protection to bribe takers should be withdrawn; a thousand or so notoriously corrupt senior civil servants in all services and tax departments should be identified by a credible and fair mechanism and all of them should be compulsorily retired under the existing powers to send a powerful signal. Wherever feasible, an executive agency system should be created similar to the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO); all senior positions should be open to the best in the country, not decided by the point of entry in a service; merit, not mere seniority should be the basis of rise in government; and there should be mandatory specialisation in civil services, not an all-purpose, unprofessional, unprepared generalist service. All this will cost no money, but will dramatically enhance the returns on what we spend on bureaucracy.

Second, rule of law is in shambles. In the police, viable measures that will transform investigation and prosecution are: separation of crime investigation from law and order, and giving complete autonomy under a State Commission’s supervision; recruitment of only officers of assistant sub-inspector (ASI) rank and above in the crime branch, enlarging the wings of the Criminal Investigation Department and enhancing skills, a well-equipped forensic laboratory in every district, an independent District Attorney drawn from judiciary to head prosecution and supervise investigation.

In the judiciary, an improvement of the Gram Nyayalayas Act and creation of about 10,000 local courts for speedy justice, more trial courts, procedural reforms in civil and criminal law, and creation of an Indian Judicial Service will ensure speedy and efficient justice that is the bedrock of a civilised society. All this will cost a paltry 0.25 per cent of GDP as additional expenditure.

Third, education and healthcare are abysmally poor, the outcomes being the worst among large economies. With no additional spend in education and at a 0.6-0.8 per cent GDP additional spend on healthcare, we can radically transform both, and help fulfill the potential of every child, reduce the burden of poverty, give opportunity to the poor and eliminate avoidable suffering.

Fourth, empower local governments by directing 33 per cent of central transfers to states directly to local governments and communities of stakeholders (ward committees and residents’ associations) at the level closest to citizens. This transfer of funds with the power to decide, execute and monitor local works and services will energise the people, promote leadership and establish a link between taxes and services. An independent, empowered Ombudsman for every district will ensure prompt corrective action in case of abuse of power or misuse of funds.

Finally, after putting in place the above four institutional reforms at a paltry additional cost of about 1 per cent of GDP, the government and opposition should work in concert to build a consensus to transform our electoral system and make the most capable public-spirited citizens electable at various levels through ethical means. Only then can we get out of the vicious cycle of poor service delivery, corruption, criminalisation, mistrust, erosion of legitimacy of authority and perpetual low-middle-income status.

Various models reducing dependence on the marginal vote and thus the need for vote buying, allowing greater stability without compromising competence and integrity, and establishing better linkage between the citizen’s vote and the outcomes (s) he experiences, making her value the vote and reduce vote buying exist. An honest dialogue among parties, a grand bargain between the union and states, and genuine, far-sighted, pragmatic systemic reforms will make honesty compatible with survival in office, enable the best to be elected by ethical means, enhance citizens’ participation and leadership development, improve service delivery and people’s satisfaction, and promote economic growth, prosperity and opportunity.

All these five are big tasks; but they are pragmatic, inexpensive, vital, achievable and broadly acceptable.

They demand political will, imagination, courage, wisdom and skill to build consensus. Now we have a priceless opportunity.

Let us tap it.

(A former Physician, J.P. is a political reformer and columnist. He is the founder of Lok Satta /Party)

Courtesy: Swaraj Magazine

We may dismiss them as unintended consequences of a momentous decision touching all people in a vast and diverse nation. But all these travails also expose the capacity deficit of the Indian State, lack of accountability, cavalier and contemptuous treatment of ordinary citizens in daily life, and the general failure of governance as perceived by the citizens. Clearly, the governance crisis cannot be effectively addressed by one person at the helm; it encompasses all branches and tiers of governance.

Those of us who are fortunate by circumstances and are insulated from the vagaries of our day-to-day governance view everything through a party-political prism. But ordinary citizens approach government offices on a daily basis for myriad services - ration card, birth certificate, record of land rights, registration of sale of a property, water or power connection, building permission, assessment of property tax, filing a first information report in a police station or going to the court in a civil dispute. In each of these instances we witness delay, harassment, humiliation, corruption, sheer incompetence and contempt for the citizen.

Almost all key services we expect the government to deliver in return for the taxes we pay - basic housekeeping, land administration, water, stormwater drainage, sewerage, electricity, traffic management, police, courts, education, healthcare - are in shambles relative to any other major economy in the world and, more important, relative to our potential and ambition as a nation. It is no wonder that almost uniquely among all major economies, Indian elites do not depend on the government for almost any service - water, power, transport, security, education, healthcare - and have gone to extraordinary lengths to insulate themselves from all-round governance failure.

This brings us to two important but related questions: Are we a singularly ungovernable people needing authoritarian political systems to control us? Is there a precipitous decline in values after Independence that brings the worst out of us and makes anarchy and corruption endemic to our society?

I argued in a 2005 paper, "Good Governance in the 21st century", that values such as honesty, trust, sacrifice, cooperation and reciprocity are very strong within a family, caste or other close-knit social groups in India, and it is not their absence that is bedeviling us. It is the incapacity to transfer these values beyond traditional groups to the larger Indian society that manifests in nepotism, corruption, criminalisation of politics and mis-governance. It is the function of the governance system to reward and encourage socially productive, desirable behaviour, and discourage deviant behaviour. As William Gladstone, the 19th century British statesman, aptly said, "the purpose of a government is to make it easy for people to do good, and difficult to do evil." It is our failure to design institutions to serve this purpose and to hold our state functionaries - politicians, bureaucrats or judges - to account that is at the heart of our crisis, not the follies of our people.

Our freedom fighters and nation builders did a remarkable job in successfully welding the world’s most diverse peoples into one nation, and building functioning democratic institutions. The results, in many ways, are astounding. Despite seemingly insurmountable obstacles, and despite being the first nation to embrace universal franchise with abject poverty and vast illiteracy, freedom has been preserved, peaceful transfer of power through the ballot has been institutionalised, a very successful and mature federalism has evolved, unity has been strengthened in a complex, unimaginably diverse, multi-ethnic, multi-lingual society and moderate economic progress has been witnessed. The way we dealt with linguistic diversity and are able to harmoniously function as one nation with 22 languages is nothing short of a miracle in the modern world, and is a tribute to our people’s common sense, pragmatism and tolerance, and our leaders’ wisdom and foresight.

Clearly, where we had designed systems well and acted with good sense, we succeeded brilliantly. The corollary is, where we designed institutions poorly and created perverse incentives, the system malfunctioned with grievous consequences.

Every society has its strengths and weaknesses. The governance system must build on strengths and correct weaknesses. In our case, certain institutional and cultural flaws that are inimical to democracy have not been adequately corrected during our republican journey, leading to the undermining of the democratic process and serious governance deficit.

We inherited three initial conditions that have not been corrected even today.

The first is asymmetry of power between the citizen and the public servant. Abject poverty, colonial legacy and a mostly agrarian economy meant that even the lowliest government employees are more economically secure, influential and powerful than most citizens. This was compounded by the disastrous license-permit-quota Raj and state control of most economic activity, and made the bureaucrat the master and the citizen the mendicant. As a result, poor delivery of services, harassment, corruption and influence peddling have become integral features of our governance.

The second initial condition is the absence of a notion of citizenship, thanks to centuries of tyranny or colonial rule, relatively sudden transfer of power from the British without real and adequate experience in self-governance, and our cultural propensity to worship hierarchies and power. As a result, elected leaders are seen as "monarchs" who will somehow deliver. Citizens were never enabled to discover the links between taxes and services, and vote and public good. Except that the new "masters" are elected, the people are still "subjects" and those in power are "mai baap".

The third initial condition is a high degree of centralisation with little space for local management of issues and no possibility of correction of distortions, leadership development or experimentation and innovation in a diverse nation.

These initial conditions led to most of our current governance crisis: over-reliance on elected legislators to somehow "deliver" with a vast parallel party machinery; failure to hold the bureaucracy to account locally and consequent poor services; vast cost of maintenance of a parallel machinery and corruption; mounting perpetual voter disaffection; use of money or short-term freebies to entice the angry voter each time; the increasing role of illegitimate money power in elections; de-linking of votes from public good and tangible consequences; manipulation of primordial loyalties and sentiments of caste, region or religion to obtain votes; political recruitment from dynasties and corrupt moneybags to somehow win power. All these are, in many ways, attributable to our failure to address the three initial conditions that are inimical to democratic governance and competent delivery.

Now that Prime Minister Modi has shown that he can break out of traditional moulds, my hope and expectation is that in 2017 and in the years after, thoughtful, systematic, innovative steps will be initiated to end this vicious cycle and generate a virtuous cycle creating the right incentives, promoting trust and citizenship, improving services and enforcing accountability. This is necessarily a slow, complex process in a vast and diverse country with enormous baggage of the past. But the positive outcomes of over two decades of partial economic reform have shown what Indians can achieve. A series of well-designed, interconnected, politically feasible, economically viable, socially acceptable institutional reforms will most certainly accelerate the emergence of this virtuous cycle and transform governance.

This essay assumes that, in the wake of demonetisation, the government will follow up on key issues of reform to end the generation of black money, especially reform in the real estate sector to help citizens come out of cash transactions, address petty corruption as well as grand corruption through a series of well-coordinated steps, and begin the process of building political consensus on creating conditions to make the best electable without vote buying.

Based on that very big assumption, here are the five big changes I would like to see in the near future.

First, improve service delivery and enforce accountability in the bureaucracy. Our service delivery is appalling and corruption is ubiquitous and endemic in almost every interface with bureaucracy. Taxation without services is nothing but legal plunder.

Willing compliance of the vast majority of citizens is the foundation of a modern state; not coercion and letting loose the arbitrary officials on the long-suffering people.

A service guarantee law should be enacted to ensure timelines and compensation for delays to end day-to-day coercive corruption and harassment; the utterly ludicrous proposals to harshly punish small bribe givers who are victims of extortion and provide protection to bribe takers should be withdrawn; a thousand or so notoriously corrupt senior civil servants in all services and tax departments should be identified by a credible and fair mechanism and all of them should be compulsorily retired under the existing powers to send a powerful signal. Wherever feasible, an executive agency system should be created similar to the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO); all senior positions should be open to the best in the country, not decided by the point of entry in a service; merit, not mere seniority should be the basis of rise in government; and there should be mandatory specialisation in civil services, not an all-purpose, unprofessional, unprepared generalist service. All this will cost no money, but will dramatically enhance the returns on what we spend on bureaucracy.

Second, rule of law is in shambles. In the police, viable measures that will transform investigation and prosecution are: separation of crime investigation from law and order, and giving complete autonomy under a State Commission’s supervision; recruitment of only officers of assistant sub-inspector (ASI) rank and above in the crime branch, enlarging the wings of the Criminal Investigation Department and enhancing skills, a well-equipped forensic laboratory in every district, an independent District Attorney drawn from judiciary to head prosecution and supervise investigation.

In the judiciary, an improvement of the Gram Nyayalayas Act and creation of about 10,000 local courts for speedy justice, more trial courts, procedural reforms in civil and criminal law, and creation of an Indian Judicial Service will ensure speedy and efficient justice that is the bedrock of a civilised society. All this will cost a paltry 0.25 per cent of GDP as additional expenditure.

Third, education and healthcare are abysmally poor, the outcomes being the worst among large economies. With no additional spend in education and at a 0.6-0.8 per cent GDP additional spend on healthcare, we can radically transform both, and help fulfill the potential of every child, reduce the burden of poverty, give opportunity to the poor and eliminate avoidable suffering.

Fourth, empower local governments by directing 33 per cent of central transfers to states directly to local governments and communities of stakeholders (ward committees and residents’ associations) at the level closest to citizens. This transfer of funds with the power to decide, execute and monitor local works and services will energise the people, promote leadership and establish a link between taxes and services. An independent, empowered Ombudsman for every district will ensure prompt corrective action in case of abuse of power or misuse of funds.

Finally, after putting in place the above four institutional reforms at a paltry additional cost of about 1 per cent of GDP, the government and opposition should work in concert to build a consensus to transform our electoral system and make the most capable public-spirited citizens electable at various levels through ethical means. Only then can we get out of the vicious cycle of poor service delivery, corruption, criminalisation, mistrust, erosion of legitimacy of authority and perpetual low-middle-income status.

Various models reducing dependence on the marginal vote and thus the need for vote buying, allowing greater stability without compromising competence and integrity, and establishing better linkage between the citizen’s vote and the outcomes (s) he experiences, making her value the vote and reduce vote buying exist. An honest dialogue among parties, a grand bargain between the union and states, and genuine, far-sighted, pragmatic systemic reforms will make honesty compatible with survival in office, enable the best to be elected by ethical means, enhance citizens’ participation and leadership development, improve service delivery and people’s satisfaction, and promote economic growth, prosperity and opportunity.

All these five are big tasks; but they are pragmatic, inexpensive, vital, achievable and broadly acceptable.

They demand political will, imagination, courage, wisdom and skill to build consensus. Now we have a priceless opportunity.

Let us tap it.

(A former Physician, J.P. is a political reformer and columnist. He is the founder of Lok Satta /Party)

Courtesy: Swaraj Magazine

Labels:

english

Friday, January 6, 2017

Tuesday, January 3, 2017

Sunday, January 1, 2017

Lok Satta Times Jan 1st-15th, 2017

Lok Satta Times Jan 1st-15th, 2017 can be downloaded from the following link.

http://ap.loksatta.org/documents/lstimes/lstimes-2017-01-01-15.pdf

http://ap.loksatta.org/documents/lstimes/lstimes-2017-01-01-15.pdf

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)